The "Northern Summit" Trip: A Journey After Thoreau

By Tamsin Venn. Photos by Tamsin Venn and David Eden.

The trip from Lobster Lake to Chesuncook via the West Branch of the Penobscot River in Maine's North Woods is a favorite for many. Lobster Lake is said to be the prettiest lake in Maine, the West Branch current moves you along on flat water with no portages and one set of mild rapids, campsites are well maintained, the river's character changes, and the views are stunning. The route is part of an ancient canoe trail used by the Wabanaki Indians (People of the Dawn) to travel the woods via lakes, ponds, rivers, and streams connected by portages.

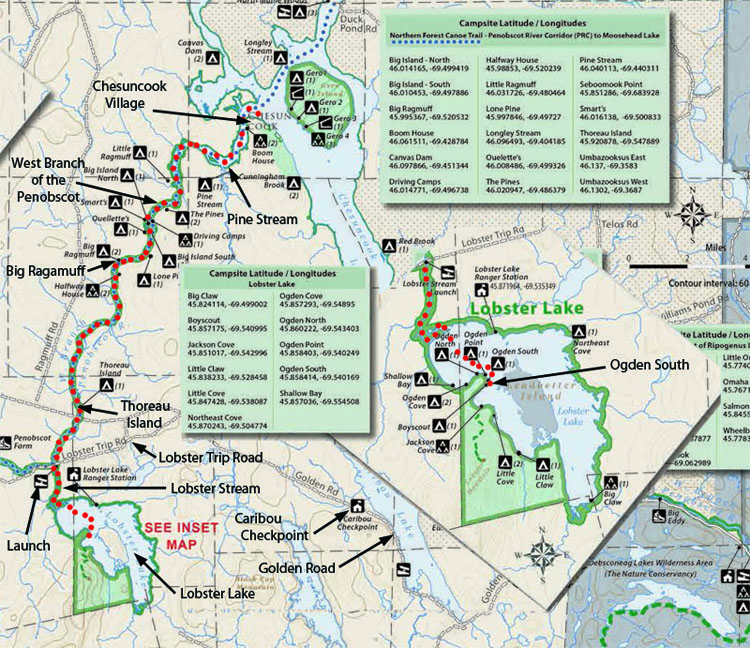

Our route in red, south to Ogden Point on Lobster Lake, then north again to Graveyard Point on Chesuncook Lake.

After many campground-based day trips in the Adirondacks with the Rhode Island Canoe & Kayak Club, we signed up for this five-day expedition led by RICKA Wilderness Chair Chuck Horbert. We felt confident that Chuck was familiar with our ways and vice versa, so confidence could be had by all without a lot of unknowns.

Before we left, Chuck let us know that the number one concern on this trip is to be safe, number two is to be safe, and number three is to have fun. We followed the prescription and ended the trip with a clean bill of health, plus many wondrous memories.

Our group would be Chuck, wife Cindy with dog Trixie, Jim Cole, me, David, and Milly, our dog. The plan was to drive to Greenville, Maine in northern Maine Tuesday, Oct. 1, spend Wednesday-Sunday on the water, four days and four nights. We would put in on Lobster Stream, head south and across Lobster Lake to camp two days; hike Lobster Mountain (2,055 feet high) for great views; day three paddle back north on Lobster Stream to the West Branch of the Penobscot to Big Ragmuff campsite, a total of 12 miles; day four nine miles to Pine Stream campsite; day five a short paddle to Graveyard Point in Chesuncook for take out. We were going to take our time, camping along the way. The current was strong due to recent rains, so we were assisted most of the way down.

For various reasons, we decide to skip the hike on Lobster Mountain and get out on the West Branch a day earlier, so we put off the 40-mile round trip shuttle to Chesuncook Village until after our night on Lobster. Chuck was very accommodating. We also had concern about the weather. The latest report was temperature drop into the 30s at night, and several days in the mid 40s, as well as possible rain and even snow. Ironically, it was Jim Cole who had come from Florida who expressed the least concern about the cold.

Day One: Lobster Lake

After spending the night in Greenville at the very basic motel and breakfast at Auntie M's, we headed out Lily Bay Road past Kokadjo and First Roach Pond, where the road turns to gravel, over Silas Hill Road to the Golden Road (see below) where we went through the Caribou Checkpoint, then left onto Lobster Lake Road, about 55 miles total to the Lobster Stream put-in, mostly on unpaved road.

The road is in pretty good shape, but Silas Hill is a bear with lots of potholes and sharp rocks. You need an updated Maine Atlas & Gazeteer. We use the National Geographic Allagash Wilderness Waterway South illustrated topographic map, which includes the back roads, is waterproof, and didn't instantly come apart at the folds, the way our Adirondack maps do. We highly recommended it.

The Lobster Stream put-in lies several miles off the Golden Road. It has a wide beach, good for launching about eight to ten boats, with large grassy parking lot which is packed in the summer. There is also a very clean outhouse. Today we are the only group at the site.

Mishaps start to occur. David tries to enter his lightweight Hornbeck canoe the recommended way by sitting sideways and flips over backwards, due to the heavy load. Strike one. Back to shore, pump out the boat, empty boots, re-enter and try again, meanwhile socks, pant legs, and amour-propre soaked. Second entry using the straddle technique is successful. Off we go, southeast to Lobster Lake, down the watery lane of spruce and fir, the sky moody and dark, the wind pushing us swiftly along.

L: The launch beach on Lobster Stream. R: David's first attempt at (over) loading leads to his first dunking. Milly does not look sanguine about our chances.

Heading upstream (uncertain, because the flow can reverse) on Lobster Stream towards Lobster Lake.

The current here is determined by the height of land. Lobster Lake and the West Branch are at a similar elevation so the current is negligible but can change direction during peak runoffs.

Did I mention this trip is also historical? Here is Henry David Thoreau's description in 1853:

"After paddling about two miles, we parted company with the explorers, and turned up Lobster Stream, which comes in on the right, from the southeast. This was six or eight rods wide, and appeared to run nearly parallel with the Penobscot. Joe said that it was so called from small fresh-water lobsters found in it. It is called Matahumkeag of the map. On account of the rise of the Penobscot, the water ran up this stream quite to the pond of the same name, or two miles. The Spencer Mts., east of the north end of Moosehead Lake, were now in plain sight in front of us. The king-fisher flew before us, the pigeon woodpecker was seen and heard, and nuthatches and chicadees close at hand. Joe said that they called the chicadee Kecunnilessu in his language."

(It should be noted that the lake has a shape very similar to that of a lobster's claw, an odd coincidence.)

Thoreau is best known for Walden, an account of his two-year retreat to the woods in a small cabin in Concord, Mass. But he also wrote several essays about the northern Maine woods to which he journeyed three times in 1846, 1853, and 1857. Posthumously a publisher collected the essays into a book - The Maine Woods. He took two trips down the West Branch to Chesuncook. His trip in 1853 started at Moosehead Lake after he took the stagecoach from Bangor.

We swiftly move 1.5 miles down to Lobster Lake following a lovely avenue of fir and spruce open to the sky, which gives way to alder and swamp as we enter the lake. Here we feel the full effect of a north wind, probably blowing ten to 15 and gusting higher. Everyone says the winds on the lakes up here can be nasty. They are right. There are wave trains coming from at least two directions. We take the whitecap waves broadside with some attempts at quartering. Our loaded Hornbecks are low to the water and vulnerable. Several waves break into David's boat. And Milly, in my boat, gets drenched. The good news is I know she won't jump out.

We move out from the protected Lobster Stream into the high, gusty winds and confusing waves of Lobster Lake.

We all intensely concentrate on the next wave to hold the boats steady, as we make our way across the northwest cirque to Ogden Point. Our plan is to round Ogden Point, then camp farther on at Little Cove for access to the trail up Lobster Mountain.

We round the point to the merciful lee, hop onto the beach. It is only then we notice that Jim is missing. We heard no call or whistle, even though the wind was blowing from him to us. Every type of disastrous scenario goes through our heads. Scanning the lake with binoculars shows no sign of Jim. It's 2:00 p.m., I say, lots of daylight left, and Cindy says, we have to find him today. Yes.

Chuck forces through dense underbrush as he follows the ledges north along shore to reconnoiter. David and I unload our boats and paddle along shore back the way we came. The boats are much more manageable unloaded. What had been a nervous slog through the waves becomes a delightful dance. We make it past several points, and around the corner comes Jim, in his steady fashion, paddling his Old Town Canoe. He had gotten tired and pulled out onto one of the other campsites for a rest, hanging his orange flag in the tree if we came looking for him.

L: The sand spit at Ogden Point. The wind here is blowing a steady 15 mph with higher gusts. R: A view of a cloud-topped Big Spencer Mountain from the spit.

L: Our tent at Ogden South. This setup, with tent and extra tarp will shelter us, with some setup variations, for the trip. R: The kitchen in the much sunnier morning of Day Two. All the campsites in this area have the tarp support poles over the tables.

Lack of cell service prevents any calls. From then on Chuck and Jim carry walkie talkies. I can vouch that none of us had ever been happier in their lives to see someone. I hug him, Cindy bursts into tears, and Jim says, "Hey, I hung the flag in the tree." Jim is a long time paddler with several wilderness adventures in this area under his paddle, including all the foibles of such. Chuck regales us with these tales every night around the campfire. In retrospect, it's not going to be easy to lose Jim.

We do not feel like budging at that point and move gear just down shore via connecting path to the more protected Ogden South campsite. Ogden Point is on a lovely sand spit with water on both sides and is great in the summer for swimming and the breezes to keep the bugs away. Today, we want to be away from the strong, cold breeze.

Ogden South has a picnic table with a tarp pole over it, fire ring, bench, and an outhouse, as do all the campsites on Lobster Lake (13 in all) and along the West Branch. (Although the outhouses we found were well-maintained, you have to take your own handcleaner and toilet paper.) The campsites are some of the nicest we have ever seen, and the rangers even leave cut and split firewood at some sites. Our menfolk do most of the splitting of the downed wood you are allowed to use (no fire permit necessary). Bring both a saw and an axe.

The view here is stunning, out to rocky islets with cormorants perched on top, the shoulder of Lobster Mountain slumping downward, bright in the flaming colors of early October. The table top of Big Spencer Mountain frames the lake, changing colors as the light fades and clouds dissipate. This is why some call Lobster Lake the most scenic lake in all of Maine.

We set up camp, fire up the two-burner Coleman. Luckily for us, Cindy and Chuck find a huge crop of edible oyster mushrooms. Cindy is an experienced mushroomer, and warns David away from the even more plentiful honey mushrooms, upsetting to some digestions. Cindy is making a group dinner tonight, so she harvests a mess and fries them in olive oil to go with her chicken sausage stir fry and fresh green beans from her garden. We are going to eat well on this trip with such additions.

L and R: Oyster Mushrooms - Pleurotus ostreatus. C: Honey Mushrooms - Armillariella tabescens. WARNING: The honey mushrooms has several near look-alikes, at least one of which is deadly poison. Never pick mushrooms for eating unless you know exactly what you are doing.

Day Two: Thoreau Slept Here

Next morning, we set out into calm water and sunshine, a welcome contrast from the day before. Behind us Spencer's summit is frosted in snow. The distant line of Mt. Katahdin (Ktaadn to Thoreau) is visible to the north. A bald eagle flies low and right over my head at Ogden Point this morning. I know it's going to be a good day.

We stop at Lobster Stream put in. The menfolk take the cars for the shuttle to Chesuncook, about 22 miles each way on gravel roads. It will be a couple of hours. Cindy and I set up camping chairs in the sun, which fortunately stays out. We witness the arrival of two groups of guys. All of a sudden things are hopping, one group headed to Lobster Lake, the other up the West Branch, mostly in kayaks. We are concerned several of the kayakers in the first group are not wearing pfds, especially after witnessing lake rage the day before. Chuck comments to them, "This must be the group leader, he's the only one wearing a pfd." No one reacts, no one puts on their pfd. Good luck with that.

L: Our first morning in camp positively sparkles. Big Spencer Mountain in the distance. R: Lobster Lake is mild after its rampaging the previous night. Mt. Katahdin in the distance.

The menfolk are back, David grousing about the dust bath he got being last in the car line. We set off, about 3.5 miles to Thoreau Island, just past the Golden Road bridge. It is a narrow island, one of two large islands on the West Branch, like a ship's prow facing upstream, parting the waters, where the campground is located.

The water is up, from recent rains, and the access is terrible, very steep. Last time Cindy and Chuck were here, they could land on a beach and had to wade out into the river and sit down in order to get wet (August). Now the river runs right by the bottom of the steep log stairs, making access tricky. We pull the boats up the steep bank after passing up the gear in fireman style, to minimize on-land injuries hauling up the bank.

Tent sites are gorgeous in a dark pine forest with cut-outs of the river gleaming through the branches, a soft bed of pine needles, and plenty of firewood. We park our chairs on the bluff and watch the West Branch swing by as afternoon deepens into early evening. The dogs romp. Milly can run freely around the island and not get lost in the wild Maine woods. Life doesn't get much better than this.

L: Milly watches Jim, Chuck, and Cindy approach the confluence of Lobster Stream and the West Branch of the Penobscot River. R: We're on the West Branch at last.

For just this short time, the West Branch is like a sheet of glass.

L: Cindy climbs up the "cliff" access to the Thoreau Island campsite. R: Fortunately, we do not find the island as wildly overgrown as Thoreau did. Quite civilized, in fact.

That night we combine our bean chili with the Horberts' buffalo chili, fry up our corn muffins, and it's a meal. Around the campfire, David reads the passage in The Maine Woods where Thoreau stays on this island for a night. The history is once again palpable, in large part because the landscape has not changed a lot from the mid 1800s when Thoreau came through here. It is difficult to think of Thoreau mooning around philosophizing when you visit visit Walden Pond in summer, when it is hopping with sunbathers, swimmers, and other visitors. Here it is more believable.

We make it to nine p.m. (This becomes a goal each night - no one can sneak off to bed before the magic hour.) It is freezing, again. I clutch the dog like an electric pad but she is small. I keep rolling off my lightweight inflatable sleeping pad. Grrr. The only drawback to this site is that you can hear occasional traffic on the nearby Golden Road.

Day Three: Thoreau Fished Here

Friday morning, 7:45 a.m. I wake to the sound of David clearing water off the tent tarp. One side a deluge, the other side a deluge. Must have poured in the night, but I slept through. Water drops sputter on the fly, don't know if it's rain or drips from the trees; I hope it's the latter. It is. In morning take-down pauses, we sit on bluff, watch the river split, swiftly move by.

The current goes one way, low mists race up the other way, like the ghosts of canoeists past. Soon the sun comes out and all is well, and we strip down; but shortly after we get on the water, clouds and wind move in and it's cold and unfriendly, and we put everything back on. Someone commented once, you can get all four seasons in one day up here.

Ghosts of canoeists past.

The river is once more a lovely avenue of spruce and fir reflected in the water, the clouds dark and wild, and it starts to rain. We stop at Halfway House camp site, about five miles up, for a rest stop and quick lunch.

We decide to keep going to the next campsite at Lone Pine to get some mileage under us. Only, this will involve going through the rapids. My throat and stomach constrict. I get a crash course in white water from all these experts: Aim for the apex, follow the downstream V, avoid pillows, follow the wave train. Last time I did whitewater was 30 to 40 years ago in northern Canada with a lot of issues. Jim helps me with training on smaller riffles.

It starts raining hard, then ice pellets. We pull over at Big Ragmuff about a half mile down, to regroup. The deciding factor is a pile of pre-chopped firewood by the fire ring left by a considerate ranger. Executive decision: we're staying. The good news is no rapids today. The bad news is rapids tomorrow.

That concern aside, Big Ragmuff is a lovely spot with two campsites right next to each other in a wooded glade, and a short walk up the trail brings you to a lovely waterfall in Ragmuff Stream. Thoreau stopped here to fish for trout with his companions when he came through.

L: A lovely avenue of spruce and fir. R: Our tentsite at Big Ragmuff right above the stream.

L: The falls on Ragmuff Stream. R: An odd fungus next to our tent.

We read more Thoreau by the campfire, this time of his climb up Mt. Katahdin. His writing can be difficult to follow, but then he nails a description or observation, it is a splendid thing. Many know his most famous quote, "in wildness is the preservation of the world." But the reading of his climb up Katahdin leads you to wonder, did he make it to the top? The answer is no.

At 9:00, we head back to the tent and are lulled to sleep by the burbling stream, until we are less than lulled, as the cold air moves in.

Day Four: Thoreau Searched for Moose Here

Next morning the sky is clear blue, frost hangs on everything. Nonetheless, I feel buoyant - the clear air, the pointy spruce, the water sailing by, reflection of a gold canopy in the water. Life is good.

Here is how Thoreau describes this section:

"My eyes were all the while on the trees, distinguishing between the black and white spruce and the fir. You paddle along in a narrow canal through an endless forest, and the vision I have in my mind's eye, still, is of the small dark and sharp tops of tall fir and spruce trees, and pagoda-like arbor vitaes, crowded together on each side, with various hardwoods intermixed."

The rapids start a mile and a half from Big Ragmuff, about 100 yards past the southern tip of Big Island where the river splits. The shallower section is on the left. We take the right.

As planned, I follow David until he gets stuck in the shoals taking photos, and then I follow Jim who very decisively points his paddle left or right in the best direction to go. He notes back in the day these were the first rapids he ever rode, and it hooked him on whitewater forever afterward. They are really fun.

A narrow canal through an endless forest.

L: The photo that grounds David in the shallows. R: Following Jim into the "rapids."

The rapids continue for longer than we anticipate and are not all that gnarly, leading to a discussion of whether these are Class One rapids or merely quickwater, probably a mix of both.

Soon we land at Little Ragmuff for a break. This is a roomy campsite, with a long and wide grassy plateau overlooking the water, not as scenic as Big Ragmuff and shaded unless you go down to the broad beach. Right after you leave Little Ragmuff you get a brief glimpse of Katahdin.

The river changes character after Big Island, which we enjoy. It's like going through different worlds, from a channel of trees and flatwater, to a channel of trees with rapids, to sand/gravel banks and rocky bluffs. Eventually the river comes more sluggish

We head off for Pine Stream campsite, our intended stop for the night, located just beyond Pine Stream, which Thoreau and his companions went up in search of moose. Thoreau like the rest of us was dying to see a moose. He was rewarded with a siting. "They made me think of great frightened rabbits with their long ears and half inquisitive and half frightened looks," he wrote.

The changing river. L: Rocky banks that Jim says were an old rapid before the Ripogenus Dam was enlarged. R: Chuck and Cindy passing a gravel and sand bar along the bank, with snow-sparkled Mt. Katahdin in the distance.

Meanwhile a situation has developed. One of the guys from the group we saw earlier passes by in an unloaded kayak. His sense of purpose is suspect as he quickly moves ahead and we guess that he is trying leapfrog us and secure the campsite at Pine Stream, to have his group's annual bonfire on the rock ledges there. After 40 minutes, we see him several hundred yards ahead. David realizes what's what as soon as we see him rush off again and paddles like hell to catch him up. He almost succeeds when the guy realizes that David is right on his tail and speeds up. The race is on!

Unfortunately, he is at least 25 years younger than David and, needless to say, he arrives at Pine Stream before us. We can hear him chopping firewood back in the forest. Chuck indicates that we have more rights as all our campers are present, with the group leader's name on the camping permit. We start to unload. The guy says you don't have to get worked up about it, then sits on the ledges and waits for the rest of his party, which trickles in over the next two hours. Awkward.

They work it out, and all is friendly in the end, even though we took their bonfire away from them. It is a spectacular spot and am glad we stayed, especially since it's not clear if the next campsite down the river will be free. The wind, which has been rising all day, has become nearly a gale, requiring some major adjustment in David's tarp design. We set up camp in various stages and a have a lovely afternoon, sitting on the bluff watching the river go by. Chuck yells, "Moose!" and we just catch sight of a huge moose with big antlers rising from the river on the far shore, then disappearing into the alders.

L: The ledges at Pine Stream are basalt beautifully glacier polished and grooved. R: Chuck splitting firewood, a daily ritual.

L: The high winds necessitates a rethink of our tarp configuration. R: Shadow pictures on the tarp in the setting sun.

Chuck contemplates the ineffable beauty of the Maine woods.

Deep dusk makes a Rorschach test at Pine Stream Camp.

I ask everyone what their highlight of the day is. For Chuck, it is getting everybody through the rapids clean; seeing the moose; and kicking everyone else off the campsite. LOL. For Jim, just being out here in the wilderness for the first time in several years. For Cindy, "being warm." For David, "at least I made that son-of-a-gun work the last two miles!"

Dinner that night is mac and cheese, with salmon, tuna, and hot dog, followed by smores. At the campfire, we no longer read Thoreau. We are Thoreau.

Day Five: Takeout at Graveyard Point

Next morning, frost is on everything. Our water jugs are frozen. The peanut butter is frozen. The water in the dog's bowl is frozen. The only items not frozen are in the coolers. The grass crackles as we walk on it. Big puffs of breath mix with the smoke from the campfire and the river is fogged. Temps must have hit the mid-20s in the night.

As we go about breakfast and take down the tents, we keep looking at the river's changing color and mood, hoping to see moose. They are active early morning and dusk. The crew scanning the river isn't lucky, but Jim sees a huge moose pass right by him near the outhouse (and stays strategically by the door until it wanders away).

We are on our way by ten. The sky is gray but the water placid, and the day serene, which is a good sign since none of us want to battle Chesuncook Lake in high winds. It's about three miles or one hour and 15 minutes to our shuttled cars at Graveyard Point.

L: Ice fog on the river Sunday morning. R: Loading up.

L to R: Milly, Tammy, David, Cindy, Trixie, Chuck, Jim.

The river is wide and sluggish, we ground out in a few places on sandy bottom. We pass the outlet for Caucomgomoc Stream which goes to the lake of the same name, another old byway.

We pass the two Boomer Island campsites and see no one there. We had expected our kicked-out party to land there, but we see them across the river on Gero Island.

Gero is a big broad island difficult to distinguish from mainland, known as the Gero Island Ecological Reserve with four campsites. Its shoreline changes from the drawdown of Chesuncook Lake, which happens in the fall to avoid spring floods. One feature on Gero is a stand of natural growth white pines with an average diameter of nearly four feet. As you round the peninsula, you get a full view of Mt. Katahdin, topped with snow.

L: Jim paddles through another Rorschach test. R: Chuck and Cindy on the last stretch.

L: The old cribs (log boom anchors) still span the West Branch near its mouth. R: Katahdin comes into view as we enter Lake Chesuncook.

We pull out at Graveyard Point in Chesuncook Village. ("A place where many streams empty in," is one of the several meanings given for the name, this one by one of Thoreau's Native guides.) We retrieve the cars in the field, load up. Chuck and Cindy will take Jim to pick up his car at Lobster Stream, then plan to exit the woods via the Golden Road to Millinocket after stopping at Abol Bridge for lunch at the restaurant there, a popular stop on the Appalachian Trail. We meet them there.

Graveyard Point is the first site of the burying place of some of the original settlers of Chesuncook Village. In 1916, when Ripogenus Dam was enlarged, increasing the size of Chesuncook Lake to 26,000 acres, the locals moved the graveyard to higher ground. Before leaving, David and I visit the old church/school and the graveyard.

Takeout on the beach at Graveyard Point

L: The old apple tree. C: The moved cemetery site. The old church/school.

When Thoreau came here in 1853, he would have found a small community starting up to support the logging industry, anchored by Ansel Smith's 80-foot-log house. Lumbermen came in winter to chop down timber, then float logs to Ripogenus Lake and down the Penobscot to Bangor in the spring. In 1971 that era ended when the Great Northern Paper Company towed the last log booms down the lake.

Many outdoor types used to stay at the Chesuncook Lake House, first built in 1863, overlooking the lake and Mt. Katahdin. It tragically burned to the ground in March of 2018. The new owners are in the process of rebuilding it, and the framing is up, to the relief of many.

Chesuncook is a time and place several degrees removed from modern life. In October the old apple trees are bearing fruit, and it is a treasure to eat one of these heirlooms, like tasting a piece of the history.

Unfortunately, the restaurant at the Abol bridge is closed, so we stop in Millinocket. Most restaurants are closed, even in major leaf-peeping season. We find the Hotel Terrace & Restaurant open and indulge in a typical post wilderness trip meal: burgers, beer, and fries, followed by the five-hour trek back to Massachuetts. Ugh.

Chuck and Cindy, followed by Jim, crossing the Abol Bridge across the West Branch downstream of Ripogenus Dam.

We will compare notes with our neighbors Peter and Alicia, who did this trip 40 plus years ago in their folding Klepper. They went by float plane from Greenville to Lobster Lake and were picked up at Chesuncook Lake. I bet not a lot has changed.

Thanks to Chuck for being such a great leader and to Cindy and Jim for being such upbeat and experienced companions. We are so lucky.

The Golden Road

Sweet to ride forth at evening from the wells,

When shadows pass gigantic on the sand,

And softly through the silence beat the bells

Along the Golden Road to Samarkand.

An extract from James Elroy Flecker's verse play, "Hassan."

The Golden Road is the privately owned 96-mile road that links Millinocket to the North Maine Woods. The 32 miles from Millinocket to Ripogenus Dam is mostly paved but the rest is gravel requiring a high clearance vehicle and 20-mph recommended speed limit (which everyone breaks). The name refers to the great cost to the Great Northern Paper Company to complete it in 1975 and then maintain it. Four companies now own the Golden Road and permit recreational users and hunters to use it for a fee, which we paid at the checkpoint. Warning: This can be a confusing process as to exactly what is owed for both the visitor and camping fee per person per night.

The main traffic are loggers; bear and moose hunters; nature watchers; and recreational users like ourselves, many of them large groups of kayakers and canoeists.

Resources:

North Maine Woods www.northmainewoods.org or (207) 435-6213. Information about camping, gates and fees, state of the roads, publishes maps/guides.

Northern Forest Canoe Trail www.nfct.org. The West Branch of the Penobscot is part of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail. Guidebook and map.

Allagash Wilderness Waterway South Trails National Geographic illustrated topographic map, waterproof, tear resistant - $11.95 on Amazon.

The Maine Atlas and Gazetteer 35th Edition, 2018 - $16.32 on Amazon.

The Maine Woods, Henry David Thoreau

Quiet Water Canoe Guide Maine, 3rd Edition. By Alex Wilson and John Hayes. Appalachian Mountain Club Books. Info on Lobster Lake. - $19.95 from AMC.